A practical guide to programmatically understanding Android app performance

The Problem Every Android Performance Engineer Knows

You open a Perfetto trace.

Thousands of slices. Dozens of threads. Millions of data points. A timeline that looks like abstract art.

And somewhere in there — buried under layers of system noise, framework callbacks, and thread interleaving — is the answer to a simple question: Why is my app slow?

I’ve spent years debugging Android performance at scale. The pattern is always the same:

- User complains about jank/slow startup

- Engineer captures a trace

- Engineer opens Perfetto UI

- Engineer spends 2 hours scrolling, zooming, and squinting

- Engineer maybe finds the root cause

Traces don’t tell stories. They dump facts — timestamped, nested, overwhelming. The gap between “having a trace” and “understanding performance” is enormous.

This article is about closing that gap programmatically.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been building a Perfetto trace analyzer that transforms raw traces into structured, human-readable insights. No dashboards. Just deterministic analysis that mirrors how experienced engineers actually reason about performance.

By the end of this article, you’ll understand how to:

- Make traces readable — startup time, long tasks, frame health

- Make traces attributable — process, thread, component ownership

- Separate responsibility — app vs framework vs system

- Use time windows to find what mattered when

- Generate deterministic suspects — prioritized signals for investigation

Why Perfetto Traces Are Hard to Read

Perfetto is incredibly powerful. It captures:

- CPU scheduling

- Frame rendering

- Binder transactions

- App-defined trace sections

- System services activity

But that power comes with complexity. A typical trace might contain:

- 50,000+ slices

- 100+ unique thread names

- Nested hierarchies 10+ levels deep

When you’re debugging a janky scroll or slow startup, you don’t need all of that. You need:

- What happened — startup time, long tasks, frame health

- Who did it — which process, which thread

- What kind of work — app code vs framework vs system

Let’s tackle these one by one.

Step 1: Making Traces Readable

The first goal is extracting high-level metrics that humans actually care about.

Startup Time

The analyzer estimates startup using a best-effort heuristic: the time from the earliest slice to the first Choreographer#doFrame.

This isn’t perfect — it doesn’t account for all startup scenarios — but it provides a useful baseline for comparison.

From a TraceToy test trace (TraceToy is a sample app I built specifically to generate interesting traces for testing — more on this later):

{

"startup_ms": 2910.15

}

In production apps, you’d typically see 500–1500ms for well-optimized cold starts, or 2000–5000ms+ for apps with heavy initialization. The exact number matters less than tracking it over time — a 20% regression is a 20% regression whether your baseline is 800ms or 3000ms.

Production apps often instrument startup more precisely — using reportFullyDrawn(), custom trace markers like Startup#complete, or libraries like Jetpack App Startup. The analyzer’s heuristic is a reasonable fallback when those aren’t available, but you can (and should) adapt it to match your app’s actual definition of “startup complete.”

One number. Immediately useful for regression detection.

Long Tasks on the UI Thread

Long tasks are slices that exceed a threshold and block the main thread. These are the primary suspects for jank and unresponsiveness.

The analyzer uses a 50ms threshold by default (configurable via –long-task-ms):

{

"ui_thread_long_tasks": {

"threshold_ms": 50,

"count": 12,

"top": [

{"name": "<internal slice>", "dur_ms": 16572.1},

{"name": "216", "dur_ms": 4103.2},

{"name": "Handler: android.view.View", "dur_ms": 312.5}

] }

}

See the problem? Numeric IDs. Internal slices. No context. No attribution.

Technically correct. Practically useless.

We know something blocked the main thread for 16 seconds. But we don’t know what or who owns it. This is where raw analysis breaks down — and why Step 2 (attribution) matters.

Frame Health

Dropped frames cause visible jank. The analyzer extracts frame timing from Choreographer#doFrame slices:

{

"frame_features": {

"total_frames": 888,

"janky_frames": 37,

"p95_frame_ms": 14.35

}

}

Percentiles matter more than averages here — a few bad frames ruin perceived smoothness even if most frames are fast.

The Limitation

At this point, we can answer: What happened?

But we can’t answer: Who’s responsible?

Step 2: Making Traces Attributable

Attribution means connecting performance data to ownership. When debugging real issues, engineers ask:

- Which process did this work?

- Which thread?

- Was it my app or something else?

Focus Process Filtering

First, we need to cut through the noise. Traces capture everything on the device — system services, other apps, kernel activity. Most of that is irrelevant.

The analyzer supports a focus mode:

python3 -m perfetto_agent.cli analyze

--trace tracetoy_trace.perfetto-trace

--focus-process com.example.tracetoy

--out analysis.json

This shifts the output from “everything happening on the device” to “what matters for this app.” A small flag with a huge impact on signal-to-noise ratio.

Process and Thread Identification

With a focus process set, every slice now gets enriched with ownership data. The analyzer joins pid and tid to process and thread names:

{

"name": "BG#churn",

"dur_ms": 267.29,

"pid": 5664,

"tid": 5664,

"thread_name": "xample.tracetoy",

"process_name": "com.example.tracetoy"

}

Compare this to the useless “name”: “216” from Step 1. Now we know:

- ✅ It’s from my app (com.example.tracetoy)

- ✅ It ran on the main thread (tid == pid)

- ✅ It’s an app-defined section (the BG# prefix)

Main Thread Detection

Here’s a subtle but important detail: the main thread isn’t always labeled “main” in traces.

The analyzer uses a best-effort heuristic:

- If a thread named “main” exists for the app process → use it

- Otherwise, fall back to tid == pid (commonly true for the main thread in Android)

This mirrors how experienced engineers reason when metadata is incomplete — and the analyzer documents which heuristic it used for transparency.

App-Defined Sections Become First-Class

Android’s Trace.beginSection() API lets developers mark custom spans:

Trace.beginSection("UI#loadUserProfile")

// ... work ...

Trace.endSection()

The analyzer extracts and aggregates these explicitly:

{

"app_sections": {

"top_by_total_ms": [

{"name": "BG#churn", "total_ms": 11811.05, "count": 194},

{"name": "UI#stall_button_click", "total_ms": 818.05, "count": 4}

] }

}

This answers: Which parts of my code dominated execution?

At this point, we’ve turned anonymous slices into attributed, actionable data. But we still haven’t answered the most important question: whose fault is it — my app, the framework, or the system?

Step 3: Separating Responsibility

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about mobile performance:

When your app is slow, not all of that work is actually yours.

Traces happily mix together:

- Your app code

- Android framework internals

- System and kernel activity

Without separating those, it’s easy to draw the wrong conclusions — and optimize the wrong thing.

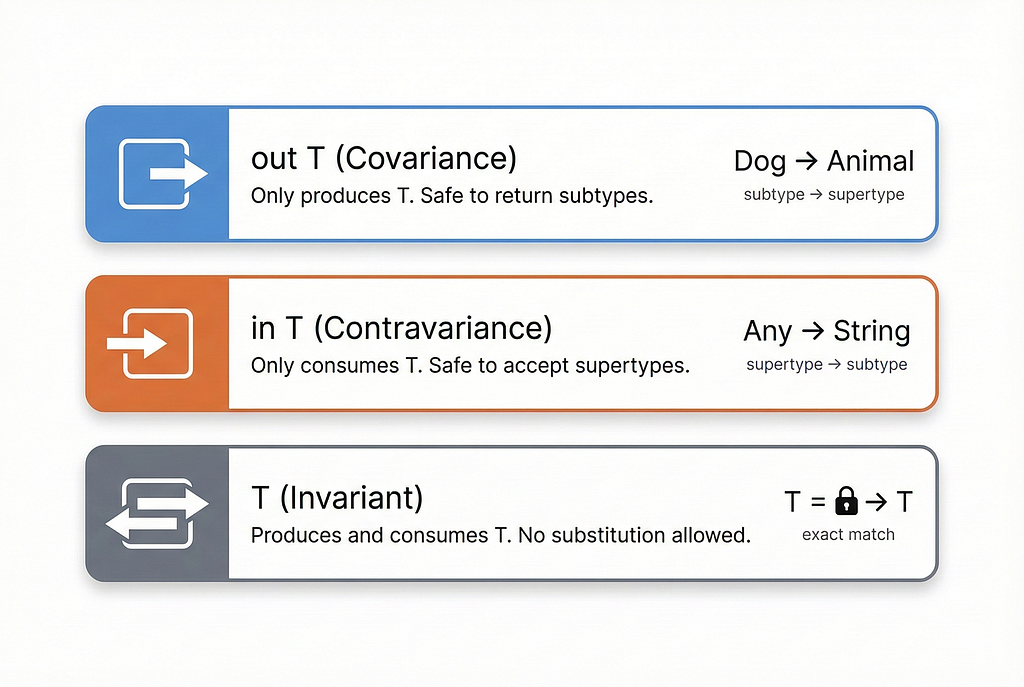

Deterministic Classification

Each slice is now labeled as one of:

- 🟢 app — App markers on the focused process (e.g., UI#stall_button_click)

- 🔵 framework — Framework tokens on the focused process (e.g., Choreographer#doFrame)

- 🔴 system — Non-focused PIDs or system tokens (e.g., binder transaction)

- ⚪ unknown — Can’t confidently classify (e.g., numeric IDs)

The classifier is intentionally conservative:

- Based on pid ownership

- Based on thread ownership

- Based on explicit name-token rules

If a slice doesn’t clearly belong to a category, it becomes “unknown”. That’s not a failure — it’s honesty.

Long Tasks with Responsibility Labels

Here’s what a classified long slice looks like:

{

"name": "BG#churn",

"dur_ms": 267.29,

"pid": 5664,

"tid": 5664,

"thread_name": "xample.tracetoy",

"process_name": "com.example.tracetoy",

"category": "app"

}

And a framework-heavy one:

{

"name": "dequeueBuffer - VRI[MainActivity]#0(BLAST Consumer)0",

"dur_ms": 180.4,

"pid": 5664,

"tid": 5688,

"thread_name": "RenderThread",

"category": "framework"

}

Same trace. Very different implications for what to optimize.

Aggregate Breakdowns

Instead of manually eyeballing hundreds of slices, the analyzer computes:

{

"work_breakdown": {

"by_category_ms": {

"app": 12603.72,

"framework": 305.77,

"system": 0.0,

"unknown": 5167.50

}

}

}

This single block answers a powerful question:

Is this performance problem primarily app-owned?

Sometimes the answer is uncomfortable. Sometimes it’s relieving. Either way, it’s grounded in data.

Main Thread Blocking: Who’s Really at Fault?

The analyzer breaks down main-thread blocking time by category:

{

"main_thread_blocking": {

"app_ms": 12603.72,

"framework_ms": 305.77,

"system_ms": 0.0,

"unknown_ms": 2840.88

}

}

This is where responsibility becomes unavoidable.

If the main thread is blocked mostly by app work (like in this trace), you know exactly where to focus optimization efforts.

The Summary Block

Everything rolls up into a minimal summary:

{

"summary": {

"main_thread_found": true,

"top_app_sections": ["BG#churn", "dequeueBuffer - VRI[MainActivity]#0...", "UI#stall_button_click"],

"top_long_slice_name": "BG#churn",

"dominant_work_category": "app",

"main_thread_blocked_by": "app"

}

}

This is not an explanation. It’s a signal — telling you where to look, and where not to.

Step 4: Time Windows and Suspects

Knowing who did the work is helpful. But performance regressions are rarely global — they’re temporal.

Typical questions sound like:

- Why was startup slow?

- Why did jank spike only after the first screen?

- Why is the UI thread blocked during interactions but not at launch?

Attribution without time context still forces you to scrub timelines manually. Step 4 reduces that cognitive load.

Time Windows: Making “When” Explicit ⏱️

Instead of treating a trace as one long timeline, the analyzer divides it into coarse, deterministic windows:

- Startup window — From process start → end of startup

- Steady-state window — The period after startup (default: 5 seconds)

{

"time_windows": {

"startup": {

"start_ms": 0.0,

"end_ms": 2910.15,

"method": "startup_ms"

},

"steady_state": {

"start_ms": 2910.15,

"end_ms": 7910.15,

"method": "startup_end + 5000ms"

}

}

}

This alone changes how you reason about a trace.

Windowed Breakdowns: Responsibility In Context 📊

For each window, the analyzer computes:

- Total work by category (app, framework, system, unknown)

- Main-thread blocking by category

From the TraceToy trace:

{

"window_breakdown": {

"startup": {

"by_category_ms": {"app": 0.0, "framework": 0.0, "system": 378.43, "unknown": 101.34},

"main_thread_blocking_ms": {"app_ms": 0.0, "framework_ms": 0.0, "system_ms": 0.0, "unknown_ms": 101.34}

},

"steady_state": { /* ... */ }

}

}

This answers, deterministically:

Startup was dominated by system work. Steady-state had significant unknown work blocking the main thread.

No guesswork required.

From Data to Suspects 🕵️

Once you have attribution, responsibility, and time windows, you can surface suspects.

A suspect is not an explanation. It’s a prioritized signal.

The analyzer generates a deterministic list:

{

"suspects": [

{"label": "Startup main thread dominated by unknown work", "window": "startup", "evidence": {"unknown_ms": 101.34}},

{"label": "Startup dominated by system work", "window": "startup", "evidence": {"system_ms": 378.43}}

// ... more suspects for steady_state

]}

These labels are templated, reproducible, and evidence-backed.

They don’t explain — they point.

The Summary Now Means Something 🧭

The summary block becomes actionable:

{

"summary": {

"startup_dominant_category": "system",

"steady_state_dominant_category": "unknown",

"top_suspect": "Startup main thread dominated by unknown work"

}

}

If you only read this, you already know:

- Where to start investigating

- What kind of work to look at

- Which phase matters most

That’s a huge shift from raw traces.

Putting It All Together

Here’s the complete workflow:

1. Capture a Trace

Use Android Studio’s profiler or the command line:

adb shell perfetto -o /data/misc/perfetto-traces/trace.perfetto-trace -t 10s

sched freq idle am wm gfx view binder_driver hal dalvik camera input res memory

2. Run the Analyzer

python3 -m perfetto_agent.cli analyze

--trace trace.perfetto-trace

--focus-process com.example.myapp

--out analysis.json

--long-task-ms 50

--top-n 10

3. Read the Output

Start with the summary block to see dominant categories and top suspects, then drill into specifics:

- work_breakdown for category distribution

- features.long_slices_attributed for individual suspects

- features.app_sections for your instrumented code

What This Is Not Doing

Let’s be clear about limitations:

- ❌ Does not assign blame — only surfaces evidence

- ❌ Does not generate advice — that requires understanding intent

- ❌ Does not claim causality — correlation isn’t causation

This system makes responsibility visible. That’s enough.

Testing with TraceToy

I built a sample app called TraceToy to generate interesting traces for testing the analyzer.

It includes:

- Startup initialization with StartupInit marker

- UI Stall button — intentionally blocks UI thread for 200ms with UI#stall_button_click

- Background load toggle — generates BG#churn markers

- Scrollable list — generates frame rendering events

Quick Start

# Record a 20-second trace

adb shell perfetto -o /data/misc/perfetto-traces/trace -t 20s sched gfx view dalvik

# Interact with the app (tap UI Stall, scroll, toggle background load)

# Pull and analyze

adb pull /data/misc/perfetto-traces/trace tracetoy_trace.perfetto-trace

python3 -m perfetto_agent.cli analyze

--trace tracetoy_trace.perfetto-trace

--focus-process com.example.tracetoy

--out analysis.json

The output should include:

- TraceToy process identified (com.example.tracetoy, pid 5664)

- BG#churn (194 occurrences, 11.8s total) and UI#stall_button_click (4 occurrences, 818ms total) in app sections

- 199 long tasks exceeding the 50ms threshold

- 888 frames with 37 janky (p95: 14.35ms)

Implementation Highlight: Slice Classification

The most interesting part of the analyzer is the classifier. It uses explicit token lists and is intentionally conservative:

def classify_slice_name(name: str | None, pid: int | None, focus_pid: int | None) -> str:

"""Classify a slice into app/framework/system/unknown using pid + name tokens."""

# If not from focus process, it's system

if focus_pid is not None and pid is not None and pid != focus_pid:

return "system"

if not name:

return "unknown"

lower_name = name.lower()

app_tokens = ["ui#", "bg#", "startupinit"] framework_tokens = [

"choreographer", "doframe", "renderthread",

"viewrootimpl", "dequeuebuffer", "blast", "hwui"

] system_tokens = ["binder", "surfaceflinger", "sched", "kworker", "irq", "futex"]

# Check app tokens first (highest confidence)

if focus_pid is not None and pid == focus_pid:

if any(token in lower_name for token in app_tokens):

return "app"

if any(token in lower_name for token in framework_tokens):

return "framework"

if any(token in lower_name for token in system_tokens):

return "system"

return "unknown"

The key insight: conservative classification beats false confidence. If we can’t confidently classify something, “unknown” is the honest answer.

See the full implementation for startup detection, main thread resolution, and frame health computation.

Instrumenting Your App

To get the most value from this analysis, instrument your code:

import android.os.Trace

class UserProfileLoader {

fun loadProfile(userId: String): UserProfile {

Trace.beginSection("UI#loadUserProfile")

try {

Trace.beginSection("UI#fetchFromCache")

val cached = cache.get(userId)

Trace.endSection()

if (cached != null) return cached

Trace.beginSection("IO#fetchFromNetwork")

val profile = api.fetchProfile(userId)

Trace.endSection()

return profile

} finally {

Trace.endSection()

}

}

}

Use a consistent naming convention:

- UI# — Main thread / UI work

- BG# — Background thread work

- IO# — I/O operations

- DB# — Database operations

This makes the analyzer’s output immediately actionable.

Try It Yourself

The analyzer is open source:

🔗 Perfetto Analyzer: github.com/singhsume123/perfetto-agent

🔗 TraceToy Test App: github.com/singhsume123/TraceToy

The repo includes:

- The Python CLI analyzer

- Example traces and outputs (analysis.json)

- Setup instructions

Key Takeaways

- Perfetto traces are powerful but overwhelming — programmatic analysis extracts signal from noise

- Attribution matters — knowing who did the work (process, thread, component) changes everything

- Separate responsibility explicitly — app vs framework vs system is the most important distinction

- Time windows matter — startup vs steady-state often have completely different characteristics

- Suspects point, not explain — deterministic signals tell you where to look first

- Conservative classification beats false confidence — “unknown” is better than wrong

- Instrument your code — Trace.beginSection() is your friend

Performance debugging is not about finding everything that happened. It’s about finding:

- What mattered

- When it mattered

- Who owned it

This analyzer makes that model explicit — and machine-readable.

Have questions or feedback? Find me on LinkedIn

Building a Deterministic Perfetto Analyzer for Android was originally published in ProAndroidDev on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This Post Has 0 Comments