Building a simple event bus to understand variance, once and for all

Introduction

Kotlin’s standard library is full of generic signatures — List<out E>, Comparable<in T>, Sequence<out T>. The in and out keywords appear constantly, but what do they actually mean? And when does a regular type parameter need one of these modifiers?

Even though generics are common in Kotlin, some of its underlying mechanics might seem fuzzy without a deeper understanding of Kotlin’s variance system, which is covered in this post.

This post builds a simple event bus from scratch. The example covers all three variance types (invariant, covariant, and contravariant) in a way that maps directly to real-world usage. The complete code is available on GitHub Gist and Kotlin Playground if you prefer to dive straight in.

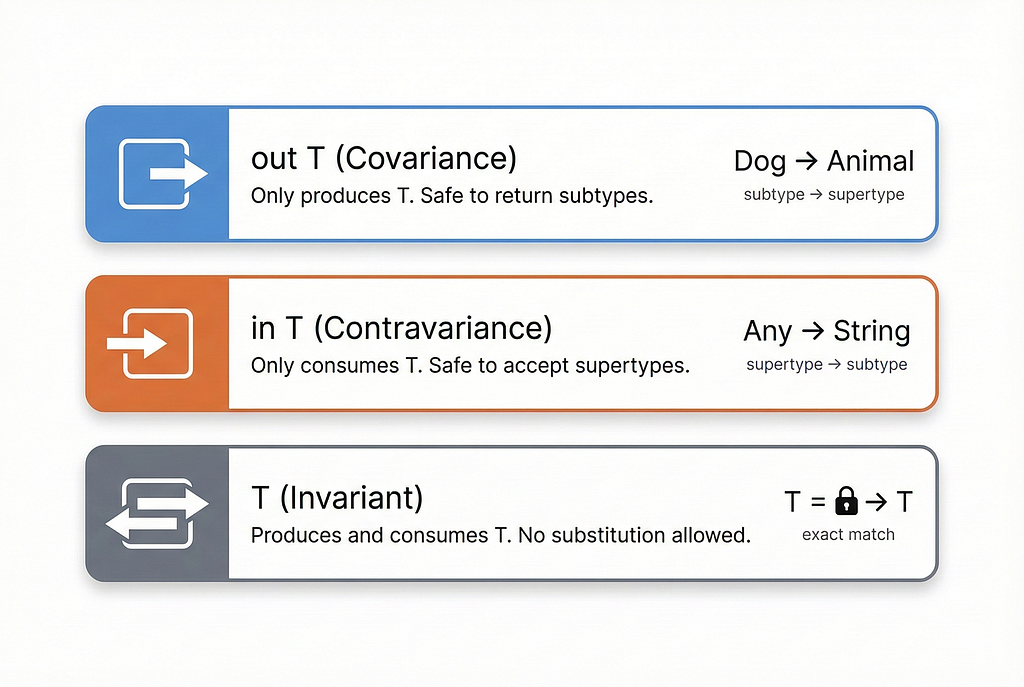

The mental model

Before diving into code, it helps to establish what variance actually controls: the direction of type substitution.

- out T (Covariance): The class only produces T, never consumes it. This makes it safe to substitute a subtype. A function returning List<out Animal> can return a List<Dog> because reading a Dog as an Animal works fine. The direction flows from specific to general: subtype → supertype.

- in T (Contravariance): The class only consumes T, never produces it. This makes it safe to substitute a supertype. A function accepting Comparable<in String> can accept Comparable<Any> because a comparator that handles any object can certainly handle strings. The direction flows from general to specific: supertype → subtype.

- T (Invariant): The class both produces and consumes T. No substitution is safe in either direction. MutableList<T> is invariant because you both read from and write to it.

The compiler enforces these constraints to prevent runtime ClassCastException errors. Java developers might recognize this pattern as PECS (Producer Extends, Consumer Super), a mnemonic introduced by Joshua Bloch in Effective Java (Item 31). Kotlin’s in and out keywords make the same concept explicit and readable.

Why EventBus

An event bus is a familiar pattern for most developers. At its core, it allows publishers to send events and subscribers to receive them. This natural separation of producers and consumers makes it an ideal example for exploring variance.

The implementation in this post is intentionally minimal: single-threaded, no external dependencies, pure Kotlin stdlib. Unlike production event buses that typically handle multiple event types through a heterogeneous map, this example uses a single-type EventBus<T> to keep the focus on variance.

Each operation maps to a different variance type: the bus itself is invariant, subscribing demonstrates covariance, and publishing demonstrates contravariance.

Building the bus

Let’s build the event bus piece by piece, examining how each component uses variance differently.

Step 1: The Invariant Start

We start with a simple container. We need to store subscribers and invoke them.

class EventBus<T> {

// Invariant: MutableMap both stores and retrieves, locking T to an exact type

private val subscribers = mutableMapOf<String, (T) -> Unit>()

}

Because MutableMap both reads and writes T, the type parameter must remain invariant. You cannot cast EventBus<Dog> to EventBus<Animal> here.

Step 2: Defining Output and Input

This is where covariance (out) and contravariance (in) come into play. To get more flexibility, we separate the “Producer” and “Consumer” roles into interfaces. This lets us take advantage of variance when passing subscriptions and consumers around.

First, the Subscription. This only provides information (like the event type) or actions (unsubscribe). It never takes a T in. It is a pure Producer.

interface Subscription<out T> {

val eventType: Class<T>

fun unsubscribe()

}

Second, the Consumer. This interface only ever accepts an event. It never returns one. It is a pure Consumer.

interface EventConsumer<in T> {

fun onEvent(event: T)

}

Step 3: Putting It Together

Now we refactor our EventBus to use these interfaces. This unlocks the variance capabilities we defined above.

class EventBus<T>(private val eventType: Class<T>) {

// Now using our variance-aware interfaces instead of raw lambdas

private val subscribers = mutableMapOf<String, EventConsumer<T>>()

fun subscribe(consumer: EventConsumer<T>): Subscription<T> {

val id = UUID.randomUUID().toString()

subscribers[id] = consumer

return object : Subscription<T> {

override val eventType: Class<T> = this@EventBus.eventType

override fun unsubscribe() {

subscribers.remove(id)

}

}

}

fun publish(event: T) {

subscribers.values.forEach { it.onEvent(event) }

}

}

We now have three variance types working in unison:

- EventBus<T> is invariant (stores and invokes)

- Subscription<out T> is covariant (only produces)

- EventConsumer<in T> is contravariant (only consumes)

The reified unlock

Generic type parameters are erased at runtime (Type Erasure). This means you normally can’t check T::class inside a generic class.

In our EventBus constructor above, we had to pass eventType: Class<T>. Kotlin’s reified keyword solves this, but it only works in inline functions.

We can create a helper function to create a bus without manually passing the class:

// inline allows us to "reify" (keep) the type T at runtime

inline fun <reified T : Any> createEventBus(): EventBus<T> {

println("Creating bus for: ${T::class.simpleName}")

return EventBus(T::class.java)

}

// Usage: No need to write (String::class.java)

val stringBus = createEventBus<String>()

This pattern appears throughout the Kotlin ecosystem, from Android’s startActivity<T>() to Koin’s get<T>(). Any API that needs runtime access to a generic type benefits from reified.

Star projection

Sometimes the specific type parameter doesn’t matter. Kotlin provides star projection <*>for these cases.

Imagine an Android ViewModel holding a list of subscriptions to various different buses. You want to unsubscribe from all of them when the screen closes. You don’t care if the subscription is for UserEvent or NetworkEvent, you just want to call unsubscribe().

// We can mix Subscription<String>, Subscription<Int>, etc.

val allSubs = mutableListOf<Subscription<*>>()

fun clearAll() {

// Safe: unsubscribe() takes no arguments

allSubs.forEach { it.unsubscribe() }

}

Subscription<*> means “a Subscription of some type, but I don’t know or care which.”

The tradeoff: you can read from a star-projected type (as Any?), but you cannot safely write to it (because the compiler doesn’t know what type it expects).

Star projection trades type specificity for flexibility.

Summary

The one rule: if you only output T, use out. If you only input T, use in. If you do both, leave it alone.

The complete EventBus implementation is available as a GitHub Gist or try it directly in the Kotlin Playground.

Understanding these concepts makes consuming APIs easier, compiler errors less mysterious, and opens the door to writing more flexible code.

in, out, reified: A Practical Guide to Kotlin Generics was originally published in ProAndroidDev on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This Post Has 0 Comments