A Deep Dive into Compiler Implementation for the Curious Android Developer

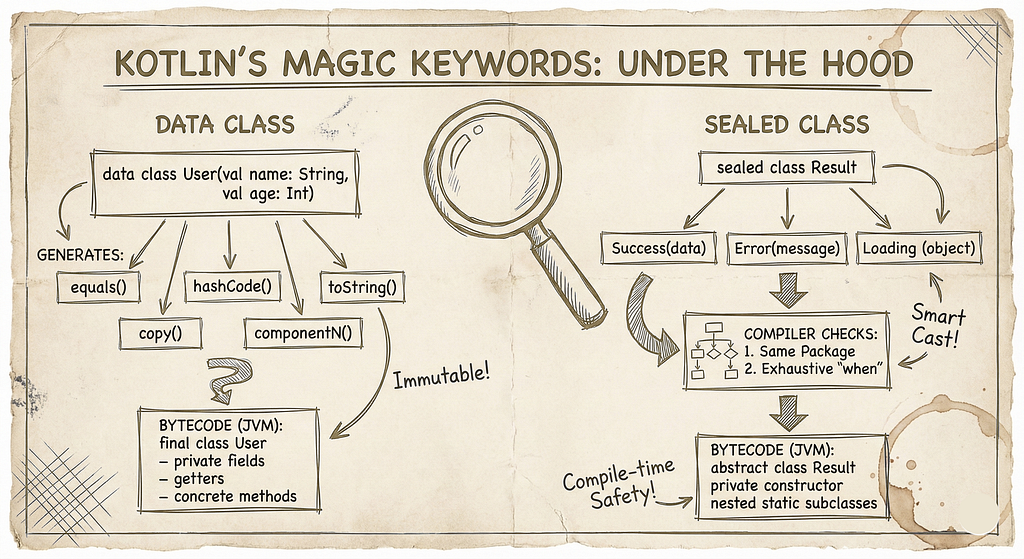

Hey! So you’ve been using data and sealed classes in your Kotlin code, and they work great. But have you ever wondered: What exactly happens when the compiler sees these keywords?

I remember when I first asked this question. I was in a code review, and a senior engineer said, “Be careful with data classes in that scenario.” I asked why, and he said, “Do you know what the compiler actually generates?”

I didn’t. And that gap in knowledge cost me a production bug later.

Today, I’m going to show you exactly what Kotlin does behind the scenes. We’ll peek under the hood, look at generated bytecode, understand the compiler’s decisions, and see why these features are designed the way they are.

By the end, you’ll:

- Understand what code the compiler generates for data classes

- Know how sealed classes are enforced at compile-time

- See the actual JVM bytecode (simplified, don’t worry!)

- Understand the performance implications

- Know exactly WHEN and WHY to use each feature

Let’s start with data classes and work our way up. Grab a coffee ☕

Part 1: What Happens When You Write data class?

The Surface Level (What You Already Know)

data class User(val name: String, val age: Int)

You know this generates equals(), hashCode(), toString(), copy(), and componentN() functions automatically. But HOW?

What the Compiler Actually Does (The Real Story)

When the Kotlin compiler sees the data keyword, it goes through a specific process. Let me show you step by step:

Step 1: Compilation Phase — AST Analysis

The Kotlin compiler first builds an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) of your code. When it encounters data class, it marks this class for special processing.

Here’s what it checks:

- Is there at least one parameter in the primary constructor?

- Are all primary constructor parameters val or var?

- Is the class not abstract, open, sealed, or inner?

- Does the class not already define these functions?

If all checks pass, it proceeds to code generation.

Step 2: Code Generation — What Gets Created

Let’s see the ACTUAL code that gets generated. Here’s our simple data class:

data class User(val name: String, val age: Int)

The compiler transforms this into something equivalent to:

class User(val name: String, val age: Int) {

// Generated: equals()

override fun equals(other: Any?): Boolean {

if (this === other) return true

if (other !is User) return false

if (name != other.name) return false

if (age != other.age) return false

return true

}

// Generated: hashCode()

override fun hashCode(): Int {

var result = name.hashCode()

result = 31 * result + age

return result

}

// Generated: toString()

override fun toString(): String {

return "User(name=$name, age=$age)"

}

// Generated: copy()

fun copy(

name: String = this.name,

age: Int = this.age

): User {

return User(name, age)

}

// Generated: component1() for destructuring

operator fun component1(): String = name

// Generated: component2() for destructuring

operator fun component2(): Int = age

}

That’s 40+ lines of code from ONE line with data! 🤯

Deep Dive: Let’s Examine Each Generated Function

1. The equals() Function: How Object Comparison Works

override fun equals(other: Any?): Boolean {

if (this === other) return true // Reference equality check

if (other !is User) return false // Type check

if (name != other.name) return false // Property comparison

if (age != other.age) return false

return true

}

What’s happening here?

Line 1: if (this === other) return true

- Uses === (reference equality)

- Checks if both variables point to the EXACT same object in memory

- This is an optimization — if they’re the same object, we don’t need to check properties

Line 2: if (other !is User) return false

- Type safety check using smart casting

- If other is not a User, they can’t be equal

- After this check, Kotlin knows other is a User

Lines 3–4: Property comparison

- Compares ONLY properties declared in the primary constructor

- Uses != which calls equals() on each property

- For primitive types (Int, Boolean, etc.), this compares values

- For objects (String, custom classes), it recursively calls their equals()

Critical Point: Properties NOT in the primary constructor are ignored!

data class Person(val name: String) {

var age: Int = 0 // This is NOT used in equals()!

}

val person1 = Person("John")

person1.age = 30

val person2 = Person("John")

person2.age = 40

println(person1 == person2) // TRUE! Age is ignored

This surprises many developers. Remember: Only primary constructor properties matter for equality.

2. The hashCode() Function: How Hash-Based Collections Work

override fun hashCode(): Int {

var result = name.hashCode()

result = 31 * result + age

return result

}

Why does this matter?

Hash code is crucial for HashSet, HashMap, and other hash-based collections. The contract is:

If two objects are equal (via equals()), they MUST have the same hash code.

The Algorithm:

- Start with the hash code of the first property

- Multiply by 31 (a prime number)

- Add the hash code of the next property

- Repeat

Why 31?

This is a famous optimization! The number 31 has special properties:

- It’s prime (reduces hash collisions)

- 31 * x can be optimized by the JVM to (x << 5) – x (bit shifting is faster)

- It’s small enough to avoid overflow issues for most cases

Real-World Impact:

val users = hashSetOf<User>()

users.add(User("John", 30))

users.add(User("John", 30)) // Won't be added - same hash code!

println(users.size) // 1, not 2

3. The toString() Function: Debugging Made Easy

override fun toString(): String {

return "User(name=$name, age=$age)"

}

Simple but powerful! This is why you can do:

val user = User("Alice", 25)

println(user) // User(name=Alice, age=25)

Without data class, you’d get: User@5e91993f (useless memory address)

Pro tip: This is automatically used by logging frameworks:

Log.d("TAG", "Current user: $user")

// Logs: Current user: User(name=Alice, age=25)

4. The copy() Function: Immutability’s Best Friend

fun copy(

name: String = this.name,

age: Int = this.age

): User {

return User(name, age)

}

This is genius! It uses Kotlin’s default parameter feature.

You can copy and modify specific properties:

val user1 = User("Bob", 30)

val user2 = user1.copy(age = 31) // Only change age

// user1 is unchanged - immutability preserved!

println(user1) // User(name=Bob, age=30)

println(user2) // User(name=Bob, age=31)

Under the hood:

- Creates a NEW object (new memory allocation)

- Copies all properties by default

- Overrides specified properties with new values

Performance consideration: Each copy() allocates new memory. For large objects or frequent copying, this can impact performance.

5. The componentN() Functions: Destructuring Magic

operator fun component1(): String = name

operator fun component2(): Int = age

The operator keyword is key here. It allows Kotlin’s destructuring syntax:

val user = User("Charlie", 35)

val (name, age) = user // Calls component1() and component2()

println(name) // Charlie

println(age) // 35

How it works:

- component1() returns the FIRST property

- component2() returns the SECOND property

- And so on… up to componentN()

Bytecode equivalent:

val user = User("Charlie", 35)

val name = user.component1()

val age = user.component2()

Important: Order matters! It’s based on the ORDER of properties in the primary constructor:

data class Person(val age: Int, val name: String)

val person = Person(25, "David")

val (first, second) = person

println(first) // 25 (age, not name!)

println(second) // David

The JVM Bytecode Level (Simplified)

Let’s peek at what the JVM actually sees. Don’t worry, I’ll explain it!

When you compile this Kotlin code:

data class Point(val x: Int, val y: Int)

The JVM bytecode (simplified) looks like:

public final class Point {

private final int x;

private final int y;

public Point(int x, int y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public final int getX() { return this.x; }

public final int getY() { return this.y; }

// equals, hashCode, toString, copy, component1, component2

// ... all generated as regular methods

}

Key observations:

- final class: Data classes are final by default (can’t be inherited)

- Private fields with getters: Kotlin properties become Java fields + getters

- All methods are concrete implementations: Nothing abstract or virtual

Performance: This compiles to the SAME bytecode as hand-written Java code. No runtime overhead!

Common Pitfalls and Gotchas

Pitfall 1: Mutable Properties Break Immutability

data class BadUser(var name: String, var age: Int)

val user = BadUser("Eve", 28)

val set = hashSetOf(user)

user.name = "EVE" // Mutated!

println(set.contains(user)) // FALSE! Hash code changed!

What happened?

- Hash code is calculated when the object is added to the set

- Mutating properties changes the hash code

- The set can’t find the object anymore!

Rule: Use val for data class properties. Always.

Pitfall 2: Large Data Classes Are Memory-Intensive

data class HugeData(

val field1: String,

val field2: String,

// ... 50 more fields

val field51: String

)

val original = HugeData(...)

val copy1 = original.copy(field1 = "new") // Copies ALL 51 fields!

val copy2 = copy1.copy(field2 = "another") // Copies ALL 51 fields again!

Each copy() creates a full new object. For large data classes with frequent copying, consider:

- Breaking into smaller data classes

- Using mutable classes where appropriate (with caution)

- Using builders for complex modifications

Pitfall 3: Deep Equality vs Shallow Equality

data class Team(val name: String, val members: MutableList<String>)

val team1 = Team("Avengers", mutableListOf("Iron Man", "Thor"))

val team2 = Team("Avengers", mutableListOf("Iron Man", "Thor"))

println(team1 == team2) // TRUE

team1.members.add("Hulk")

println(team1 == team2) // FALSE! List contents changed

Data class equality is “shallow” for collections:

- It checks if the list OBJECTS are equal

- For mutable lists, equality checks the current contents

- Modifying the list changes equality

Best practice: Use immutable collections in data classes:

data class Team(val name: String, val members: List<String>) // Immutable List

Part 2: What Happens When You Write sealed class?

Now let’s dive into the second keyword: sealed.

The Surface Level (What You Already Know)

sealed class Result {

data class Success(val data: String) : Result()

data class Error(val message: String) : Result()

object Loading : Result()

}

You know sealed classes restrict subclasses and enable exhaustive when expressions. But HOW does the compiler enforce this?

What the Compiler Actually Does (The Real Story)

Step 1: Compilation Phase — Visibility and Location Checks

When the Kotlin compiler sees sealed class, it performs strict checks:

Check 1: Subclass Location

- In Kotlin 1.0–1.4: All subclasses MUST be in the same file

- In Kotlin 1.5+: All subclasses MUST be in the same package (same module)

Check 2: Constructor Visibility

- Sealed class constructors are ALWAYS private or protected

- You cannot make them public

Check 3: Direct Subclasses Only

- The compiler tracks only DIRECT subclasses

- Subclasses of sealed class subclasses are not restricted

Let me show you what this means:

// File: Result.kt

sealed class Result {

data class Success(val data: String) : Result() // ✅ Same file

data class Error(val message: String) : Result() // ✅ Same file

}

// File: AnotherFile.kt

class Timeout : Result() // ❌ COMPILE ERROR! Different file

Why this restriction?

The compiler needs to know ALL possible subclasses at compile time to enable exhaustive checking. If anyone could extend the sealed class from anywhere, the compiler couldn’t guarantee exhaustiveness.

Step 2: How Exhaustive when Works

Here’s the magic part. Let’s look at this code:

fun handleResult(result: Result) {

when (result) {

is Result.Success -> println("Success: ${result.data}")

is Result.Error -> println("Error: ${result.message}")

is Result.Loading -> println("Loading...")

}

}

No else branch needed! How does Kotlin know all cases are covered?

The Compiler’s Process:

- Sealed Class Metadata: When compiling Result, the compiler creates metadata listing all direct subclasses:

- Result -> [Success, Error, Loading]

2. When Expression Analysis: When compiling the when expression, the compiler:

- Checks if the subject is a sealed class

- Retrieves the list of all subclasses from metadata

- Verifies each subclass is handled

3. Exhaustiveness Check:

- Branches checked: [Success, Error, Loading] All subclasses: [Success, Error, Loading] Match? YES ✅ -> Exhaustive!

4. If Not Exhaustive:

- when (result) { is Result.Success -> println(“Success”) // Missing Error and Loading! } // ❌ COMPILE ERROR: ‘when’ expression must be exhaustive

Step 3: The Bytecode Reality

Here’s what’s fascinating: At the JVM bytecode level, sealed classes are just regular classes!

sealed class Result {

data class Success(val data: String) : Result()

object Loading : Result()

}

Compiles to (simplified):

public abstract class Result {

private Result() {} // Private constructor!

public static final class Success extends Result {

private final String data;

// ... constructor, getters, etc.

}

public static final class Loading extends Result {

public static final Loading INSTANCE; // Singleton

static {

INSTANCE = new Loading();

}

}

}

Key points:

- Abstract class: Sealed classes become abstract classes in bytecode

- Private constructor: Prevents external instantiation

- Nested classes: Subclasses become static nested classes

- Metadata annotations: Kotlin adds special annotations for tooling

The enforcement is COMPILE-TIME only! At runtime, it’s just a regular class hierarchy.

Deep Dive: How Exhaustiveness Actually Works

Let’s see a concrete example of how the compiler tracks this:

sealed class State {

object Idle : State()

object Loading : State()

data class Success(val data: String) : State()

data class Error(val error: String) : State()

}

fun render(state: State) {

when (state) {

is State.Idle -> showIdle()

is State.Loading -> showLoading()

is State.Success -> showSuccess(state.data)

is State.Error -> showError(state.error)

} // ✅ Exhaustive!

}

Now let’s add a new state:

sealed class State {

object Idle : State()

object Loading : State()

data class Success(val data: String) : State()

data class Error(val error: String) : State()

object Refreshing : State() // NEW!

}

fun render(state: State) {

when (state) {

is State.Idle -> showIdle()

is State.Loading -> showLoading()

is State.Success -> showSuccess(state.data)

is State.Error -> showError(state.error)

} // ❌ COMPILE ERROR! Missing: Refreshing

}

The error message you’ll see:

'when' expression must be exhaustive, add necessary 'is Refreshing' branch or 'else' branch instead

This is powerful! The compiler is your safety net. You can’t forget to handle a case.

The Real Power: Smart Casting

Here’s something subtle but important. Notice in the when expression:

when (state) {

is State.Success -> showSuccess(state.data) // 'state' is smart-cast to Success!

is State.Error -> showError(state.error) // 'state' is smart-cast to Error!

}

You don’t need to cast manually! The compiler does it automatically:

// You DON'T need this:

is State.Success -> {

val success = state as State.Success

showSuccess(success.data)

}

// Kotlin does it for you:

is State.Success -> showSuccess(state.data) // state.data is accessible directly!

How does this work?

- Type Narrowing: After the is check, the compiler knows the exact type

- Flow-Sensitive Typing: Within that branch, the type is narrowed

- Safe Access: Properties specific to that subclass are now accessible

This is called Flow-Sensitive Smart Casting, and it’s one of Kotlin’s killer features.

Sealed Classes vs Enums: The Key Difference

People often ask: “Why not just use an enum?”

enum class ResultType {

SUCCESS, ERROR, LOADING

}

The critical difference: Enums can’t hold data!

// ❌ Can't do this with enum:

enum class Result {

SUCCESS("data goes here?"), // Each instance is the same type!

ERROR("how to store different data?")

}

// ✅ Sealed classes can:

sealed class Result {

data class Success(val data: String) : Result() // Different data!

data class Error(val exception: Exception) : Result() // Different data!

}

At the bytecode level:

Enum:

public final class ResultType extends Enum<ResultType> {

public static final ResultType SUCCESS = new ResultType("SUCCESS", 0);

public static final ResultType ERROR = new ResultType("ERROR", 1);

// All instances have the same structure

}

Sealed Class:

public abstract class Result {

public static final class Success extends Result {

private final String data; // Custom data!

}

public static final class Error extends Result {

private final Exception exception; // Different data!

}

}

When to use each:

- Enum: Fixed set of constants (no associated data)

- Example: enum class Direction { NORTH, SOUTH, EAST, WEST }

- Sealed Class: Fixed set of types with associated data

- Example: sealed class ApiResult<T> { data class Success<T>(val data: T), data class Error(val e: Exception) }

Performance Implications

Memory Overhead

Data classes:

- Same memory as regular classes

- Each copy() creates a new object (GC pressure if overused)

Sealed classes:

- Same as regular class hierarchy

- object subclasses are singletons (one instance total)

- data class subclasses have standard data class overhead

Runtime Performance

Both have ZERO runtime overhead compared to hand-written code:

- No reflection involved

- No dynamic dispatch overhead

- Compiled to standard JVM bytecode

When expressions on sealed classes:

- Compiled to efficient bytecode (usually a tableswitch or lookupswitch)

- Similar performance to if-else chains

- No runtime type checking beyond standard JVM

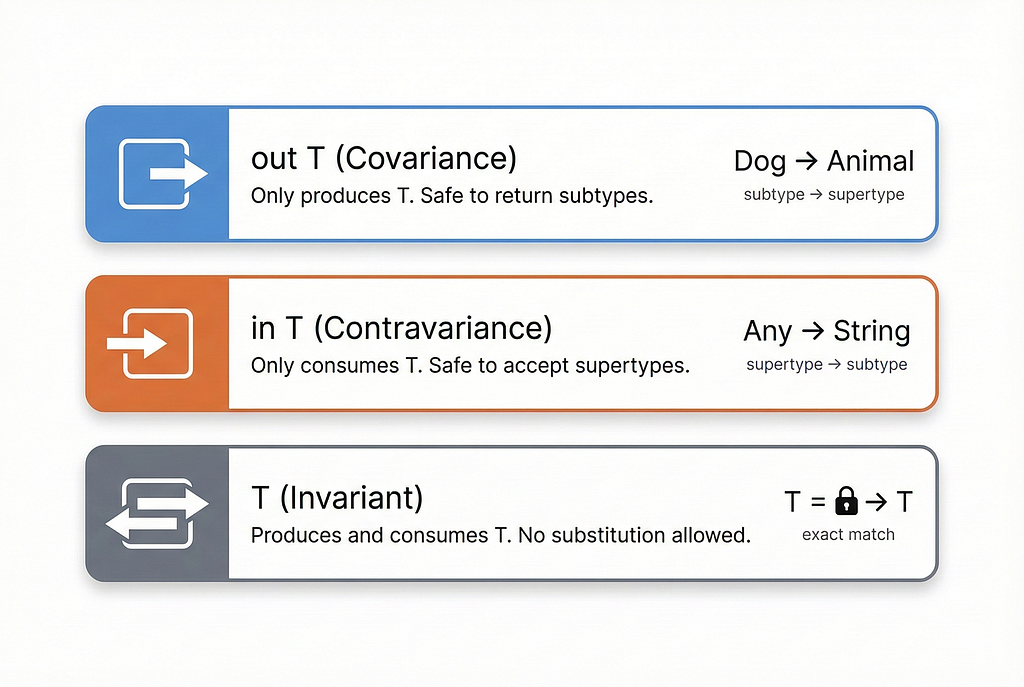

Advanced: Sealed Interfaces (Kotlin 1.5+)

sealed interface Command

data class LoadUser(val id: String) : Command

data class SaveUser(val user: User) : Command

sealed interface Event

object UserLoggedIn : Event

object UserLoggedOut : Event

// A class can implement multiple sealed interfaces!

data class UserAction(val userId: String) : Command, Event

Why interfaces?

Sealed classes can only extend one class (single inheritance), but can implement multiple interfaces. Sealed interfaces give you more flexibility.

Bytecode difference:

public interface Command { // Interface instead of abstract class

// Kotlin metadata indicates it's sealed

}

Part 3: The Design Philosophy

Why These Design Decisions?

Let me share some history.

Data Classes: The “Stop Writing Boilerplate” Philosophy

Java’s pain point:

// Java

public class User {

private final String name;

private final int age;

public User(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

// 40 more lines of equals, hashCode, toString, getters...

}

Kotlin’s solution: Make the common case trivial

data class User(val name: String, val age: Int)

Design principle:

“If 95% of value classes need the same methods, generate them automatically. Let developers override when needed.”

Sealed Classes: The “Make Illegal States Unrepresentable” Philosophy

Before sealed classes:

// Error-prone approach

class Result(

val isLoading: Boolean,

val data: String?,

val error: String?

)

// Impossible states are possible!

val impossible = Result(isLoading = true, data = "data", error = "error")

After sealed classes:

sealed class Result {

object Loading : Result()

data class Success(val data: String) : Result()

data class Error(val error: String) : Result()

}

// Impossible states are now IMPOSSIBLE to represent!

Design principle:

“Use the type system to prevent bugs at compile time, not runtime.”

Common Interview Questions (And How to Answer Them)

Q1: “What’s the performance cost of data classes?”

Answer: “Data classes have the same runtime performance as hand-written classes. The compiler generates standard methods — equals, hashCode, toString, copy, and componentN functions. There’s no reflection or runtime overhead. However, the copy() function creates a new object, which can create GC pressure if used frequently on large objects. For high-performance scenarios with frequent modifications, consider using builders or mutable classes instead.”

Q2: “Why can’t I inherit from a data class?”

Answer: “Data classes are implicitly final because inheritance would break the generated equals() and copy() methods. If a subclass added new properties, equals() from the parent wouldn’t compare them, leading to incorrect behavior. If you need inheritance, remove the data keyword and write methods manually, or consider composition over inheritance.”

Q3: “How does the compiler know all sealed class subclasses?”

Answer: “The compiler enforces that all direct subclasses of a sealed class must be in the same package (same module in Kotlin 1.5+). During compilation, it builds a complete list of subclasses and stores this as metadata. When compiling a when expression on a sealed class, it checks this metadata to verify all cases are handled, enabling exhaustiveness checking without requiring an else branch.”

Q4: “What’s the difference between sealed classes and abstract classes?”

Answer: “Both can’t be instantiated directly, but sealed classes restrict WHERE subclasses can be defined — they must be in the same package. Abstract classes allow subclasses anywhere. This restriction allows the compiler to know all possible subclasses at compile time, enabling exhaustive when expressions. Sealed classes are for closed hierarchies; abstract classes are for open hierarchies.”

Wrapping Up: Key Takeaways

Data Classes

What the compiler does:

- Generates equals(), hashCode(), toString(), copy(), componentN() functions

- Based ONLY on primary constructor properties

- Creates standard JVM bytecode — no runtime overhead

When to use:

- Value objects (DTOs, API responses, database entities)

- When you need structural equality

- When immutability is important

Watch out for:

- Mutable properties (use val)

- Large objects with frequent copying

- Properties outside primary constructor (ignored by generated methods)

Sealed Classes

What the compiler does:

- Enforces subclass location restrictions (same package/module)

- Builds compile-time registry of all subclasses

- Enables exhaustive when expressions

- Performs smart casting in branches

When to use:

- Representing a fixed set of types

- State management (Loading, Success, Error)

- When exhaustive handling is critical

Watch out for:

- Can’t be extended outside the package

- Runtime performance is same as regular classes

- Use sealed interface for multiple inheritance

The Real Power: Compile-Time Safety

Both features share a common philosophy: Move errors from runtime to compile time.

- Data classes: Compiler ensures consistent equality/hashing behavior

- Sealed classes: Compiler ensures all cases are handled

This is what makes Kotlin different from Java. The compiler is your friend, catching bugs before your users do.

Further Exploration

Want to see the actual bytecode? Try this:

- Compile your Kotlin file: kotlinc MyFile.kt

- Decompile with: javap -c MyFileKt.class

- Or use IntelliJ: Tools → Kotlin → Show Kotlin Bytecode → Decompile

You’ll see exactly what we discussed!

That’s the deep dive! You now understand not just WHAT these keywords do, but HOW they work under the hood. Next time someone asks you in an interview or code review, you’ll know exactly what’s happening at every level — from source code to bytecode.

Now go write some great Kotlin code! 🚀

Happy coding! 💻

The Magic Behind Kotlin’s data and sealed Keywords: What Really Happens Under the Hood was originally published in ProAndroidDev on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This Post Has 0 Comments